As part of our Pasture Renovation project last fall and into this year, supported by NRCS (Natural Resources Conservation Service) we installed two Soil Moisture sensors and a flowmeter. (If you want to start from the beginning to see photos of this project search in the blog for the topic, Pasture and Irrigation Renovation.) The goal of having these sensors is to aid in planning the timing of irrigation. However I find it interesting to see what is going on now with the rain.

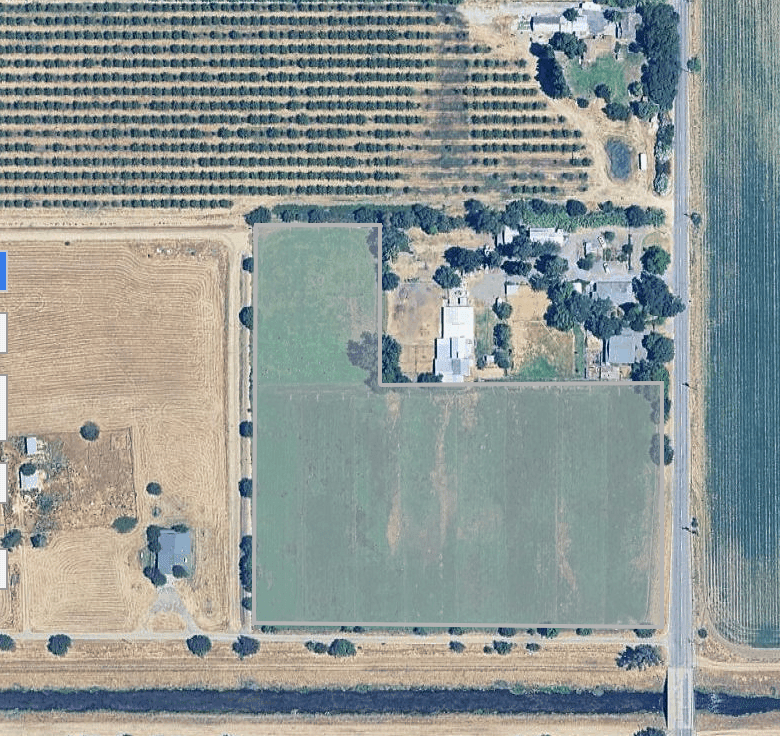

I took the photo below from the website we use to read the soil moisture info. I thought it would be interesting to see the aerial view of the farm. Our 10-acre farm is the green square in the center (plus buildings). There is an almond orchard north of us and alfalfa on the east. When I write about Across the Road that is what I’m talking about. There is a large canal on the south just past the driveway that leads to the neighbors on the west. This photo is from before we did the work in 2024 and still had an open ditch for irrigating. You can tell that we had eight fence lines in the south pasture. There are now nine interior fence lines running north-south, each 60′ apart. There are valves in the new irrigation pipeline every 30′, so when I graze I can either graze the 60′ wide strip or split that into two 30′ wide paddocks.

This photo provides a good visual for the post I wrote (and plan to do more) about sheep grazing Across the Road. The trucks in that post were parked just across the main road and between the trees just south of the house on our side of the road and the bushes on the other side just south of our tree.

Back to the purpose of this post, the soil moisture sensors.

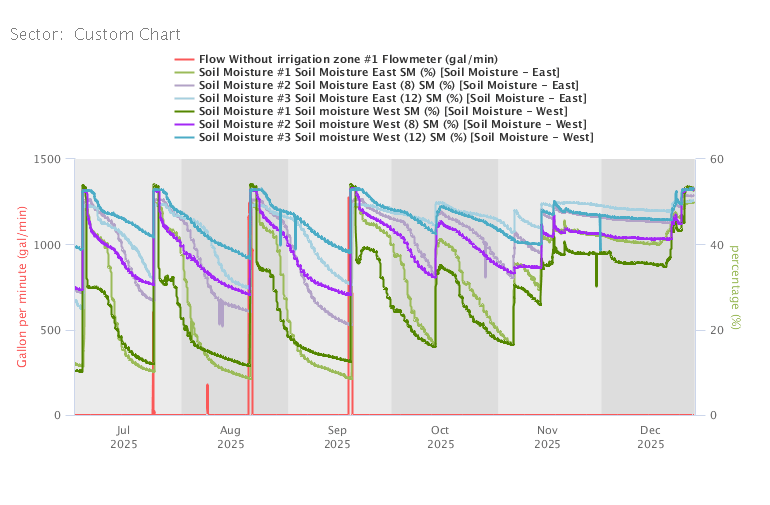

Let me explain what you’re seeing. The red line is the flow meter. It’s at zero except when we are irrigating. That shows the water coming into the pipeline from SID (Solano Irrigation District). It took some tweaking to get it right. The July reading stopped but we didn’t know why. By early August we had the solution. We needed a screen over the intake area so that weeds and branches didn’t physically impede the propellor going around in the pipeline.

About the other colors. There are two soil moisture sensors. Both are at the south end of the pasture. Now that I have added the aerial photo I can refer you to that–southwest corner and south edge about 2/3 of the way to the east. They are not right on the south fence line but about 20′ north of that.

Each sensor measure soil moisture at three depths–4″, 8″, and 12″. The goal is to know the moisture in the root zone of the pasture plants. Those depths are color coded: green is 4″, purple is 8″, and blue is 12″. When I look at the chart I have to orient myself to know that I’m not seeing the soil profile as it is if I am standing there. I think it as green for the plants and blue for the deepest water. Then it makes sense. The darker colors are the sensor on the west and the lighter colors are the east sensor. So you can see that when we irrigate or it rains all levels being measured are mostly saturated. The 4″ depth dries out most quickly while it takes longer for the other two to lose moisture, and during the summer they don’t lose nearly as much moisture as the ones closer to the surface.

November 13 and 14 it rained about 2″. The weather stayed foggy for weeks after that and into December. The soil moisture level remained high. I assume that is because #1- It was so foggy and damp, and #2 – plant demand slowed way down because of the cold and the season.

To be thorough I thought I’d show you most of the year. Early May shows our first irrigation. We were having the problem with the flowmeter but didn’t figure out the solution until August.

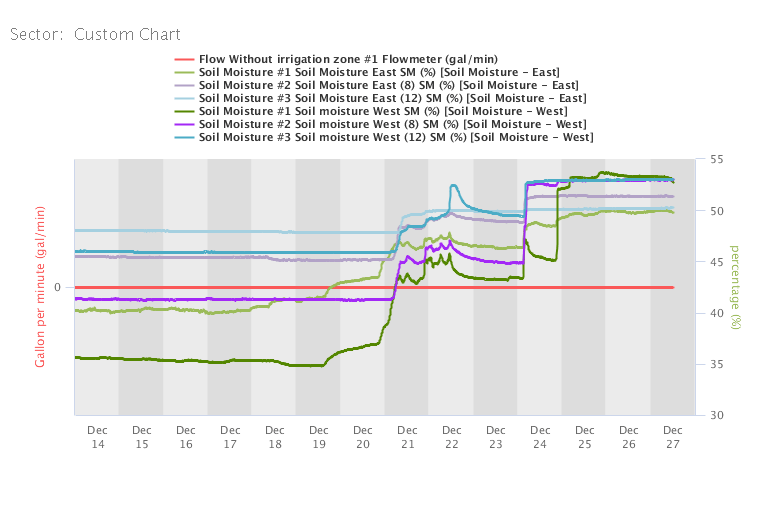

This view of the last two weeks makes it easier to see what’s going on. This explains why I have the sheep blocked off the pasture now. It is very wet, and I think it is better for the sheep and the pasture to have them off of it. It’s not that sheep can’t handle some rain, but, just like you don’t stomp around in your vegetable garden when you’re irrigating, we don’t want to impact the soil as 60 sheep (240 hooves) would.

Now I’ve convinced myself that I made the right decision to lock them in for now.

I irrigated this weekend. The sheep were just moved off the paddock to the right and when it dries up enough they will go on the one to the left. Can you see the difference? It took only two days for them to eat that feed.

I irrigated this weekend. The sheep were just moved off the paddock to the right and when it dries up enough they will go on the one to the left. Can you see the difference? It took only two days for them to eat that feed. One of their favorite plants is Birdsfoot Trefoil. It is a legume which means it is one of the plants that converts nitrogen in the air to a form that can be used by the plant. It is actually not the plant that does that but the bacteria that live in nodules on the roots of legumes.

One of their favorite plants is Birdsfoot Trefoil. It is a legume which means it is one of the plants that converts nitrogen in the air to a form that can be used by the plant. It is actually not the plant that does that but the bacteria that live in nodules on the roots of legumes. Clovers are also legumes. This is a variety of white clover.

Clovers are also legumes. This is a variety of white clover. This morning I noticed just a few of these flowers. I can’t decide if this is a variant of the white clover or is a different species. The leaves are similar. I’ll have to do some more checking.

This morning I noticed just a few of these flowers. I can’t decide if this is a variant of the white clover or is a different species. The leaves are similar. I’ll have to do some more checking. Do you see how most of the other plants have been eaten and this one has not been touched? The sheep avoid plants that are toxic to them. This is Narrow-leaved Milkweed (Asclepias fascicularis). Not only is it a favored species for the monarch butterfly but according to a

Do you see how most of the other plants have been eaten and this one has not been touched? The sheep avoid plants that are toxic to them. This is Narrow-leaved Milkweed (Asclepias fascicularis). Not only is it a favored species for the monarch butterfly but according to a  These are Narrow-leaved Milkweed flowers in various stages…

These are Narrow-leaved Milkweed flowers in various stages… …and a close-up.

…and a close-up. Field bindweed (Convolvulaceae arvensis), also known as morning glory. It is, according to a

Field bindweed (Convolvulaceae arvensis), also known as morning glory. It is, according to a  Soft Chess or Soft Brome, a non-native annual grass.

Soft Chess or Soft Brome, a non-native annual grass.

Medusahead as it is drying out. Medusahead covers thousands of acres of California foothills. It is not normally found in irrigated pasture, but it is in the easternmost paddock here which sometimes does not irrigate well. I have reclaimed part of that paddock, but I continually fight this plant. I find patches of it in other areas of the pasture and, although this is not an effective control technique, I pull it up by the handfuls as I walk by, coming back to the barn with it stuffed in the pockets of my overalls. It is a nasty plant that is “…among the worst weeds: not only does medusahead compete for resources with more desirable species, but it changes ecosystem function to favor its own survival at the expense of the entire ecosystem…Because grazing animals selectively avoid this plant, and because medusahead thatch tends to suppress desirable forage species, infestations often develop into near-monotypic stands.” From the

Medusahead as it is drying out. Medusahead covers thousands of acres of California foothills. It is not normally found in irrigated pasture, but it is in the easternmost paddock here which sometimes does not irrigate well. I have reclaimed part of that paddock, but I continually fight this plant. I find patches of it in other areas of the pasture and, although this is not an effective control technique, I pull it up by the handfuls as I walk by, coming back to the barn with it stuffed in the pockets of my overalls. It is a nasty plant that is “…among the worst weeds: not only does medusahead compete for resources with more desirable species, but it changes ecosystem function to favor its own survival at the expense of the entire ecosystem…Because grazing animals selectively avoid this plant, and because medusahead thatch tends to suppress desirable forage species, infestations often develop into near-monotypic stands.” From the  I have ID’d this one as Blunt Spikerush (Eleocharis obtusa), not a grass, but a sedge that is found on poorly drained soil and marshy areas. That’s my pasture…poorly drained soil. There is a lot of this sedge in the middle and south end of three or four of the paddocks. It looks like foot-tall grass, but that is why it is important to actually look at what is out there. This does not make good forage.

I have ID’d this one as Blunt Spikerush (Eleocharis obtusa), not a grass, but a sedge that is found on poorly drained soil and marshy areas. That’s my pasture…poorly drained soil. There is a lot of this sedge in the middle and south end of three or four of the paddocks. It looks like foot-tall grass, but that is why it is important to actually look at what is out there. This does not make good forage. A rather artsy shot of Buckhorn Plantain, found throughout California…

A rather artsy shot of Buckhorn Plantain, found throughout California… …and a photo in which you will probably more easily recognize it.

…and a photo in which you will probably more easily recognize it. This was taken from standing in the northwest corner of the property and looking west. When SID (Solano Irrigation District) opens the right gate the water comes down that canal, through a gate in the cement structure at the bottom of the photo and…

This was taken from standing in the northwest corner of the property and looking west. When SID (Solano Irrigation District) opens the right gate the water comes down that canal, through a gate in the cement structure at the bottom of the photo and… …comes up through this standpipe. It goes out that hole on the left and…

…comes up through this standpipe. It goes out that hole on the left and… into this ditch. At the end of the ditch it turns south and goes into the other part of the pasture. Later in the year this ditch will require weed-wacking for the whole length to allow the water to flow. This time I didn’t need to do that.

into this ditch. At the end of the ditch it turns south and goes into the other part of the pasture. Later in the year this ditch will require weed-wacking for the whole length to allow the water to flow. This time I didn’t need to do that. This part of the ditch has old pipes that take the water under the burm. I can find two of the three that used to be functional.

This part of the ditch has old pipes that take the water under the burm. I can find two of the three that used to be functional. The first job is to dig out around both ends of these.

The first job is to dig out around both ends of these. As I walk through the pasture I find thistles that need to be chopped.

As I walk through the pasture I find thistles that need to be chopped. The rest of the pasture doesn’t have those pipes, but instead has cut-outs or places where the burm is cut away to allow the water to flow from the ditch into the pasture. I didn’t get photos of those. This photo is a cut-out (under the fence) that I had to fill in because it was where we had cut through the burm to allow water flow INTO the ditch in the winter to help drain the rainwater that was all around the barn.

The rest of the pasture doesn’t have those pipes, but instead has cut-outs or places where the burm is cut away to allow the water to flow from the ditch into the pasture. I didn’t get photos of those. This photo is a cut-out (under the fence) that I had to fill in because it was where we had cut through the burm to allow water flow INTO the ditch in the winter to help drain the rainwater that was all around the barn.  Here is the place at the northeast corner of the pasture where I have to put a tarp to keep the water backed up in the ditch. After this point the ditch turns south and drains at the southeast corner of the property.

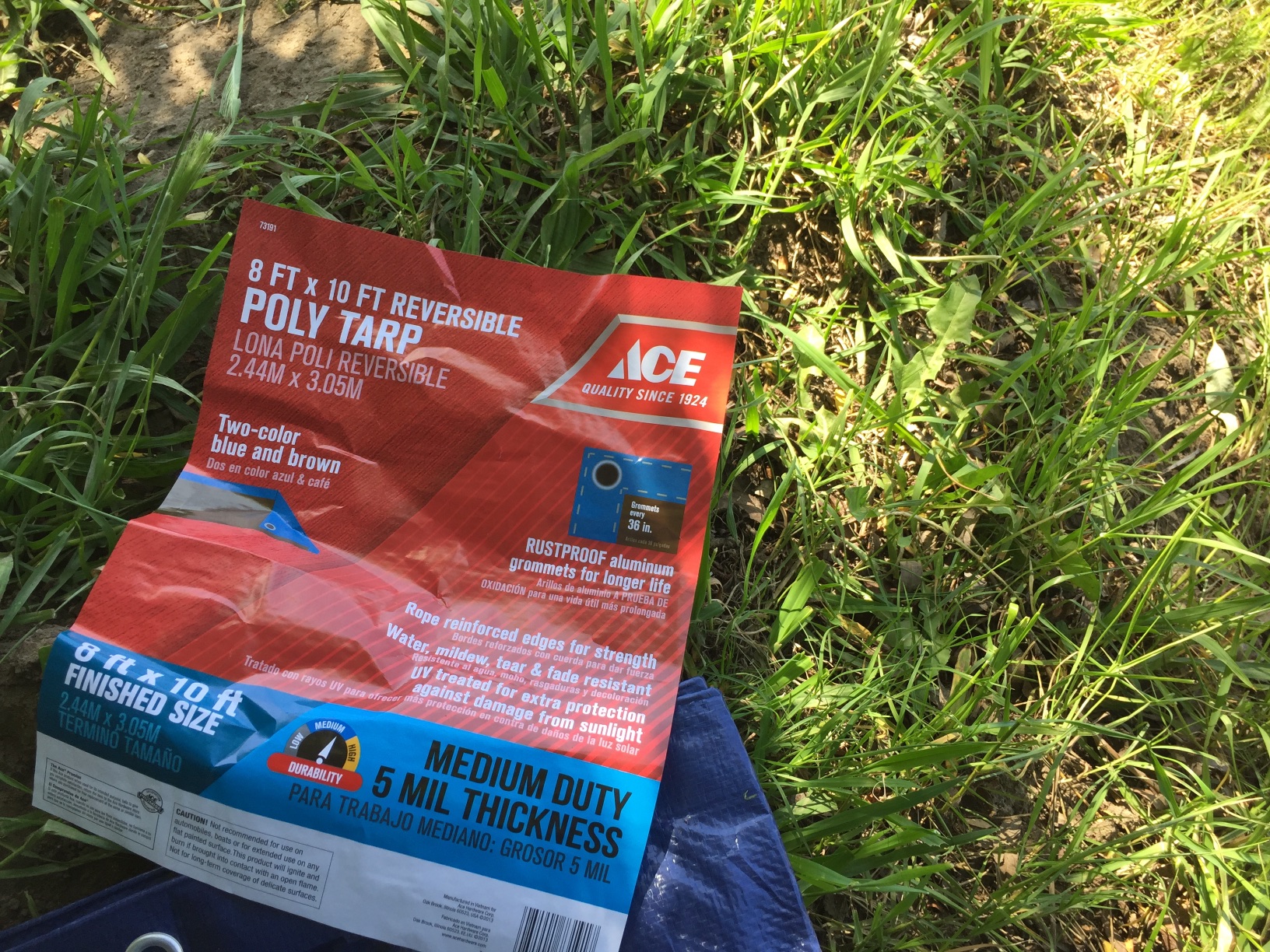

Here is the place at the northeast corner of the pasture where I have to put a tarp to keep the water backed up in the ditch. After this point the ditch turns south and drains at the southeast corner of the property. I can never remember what size tarp to get. I bought 2 sizes and took this photo to remind myself that this one is just fine.

I can never remember what size tarp to get. I bought 2 sizes and took this photo to remind myself that this one is just fine. The idea is to set the tarp so that the edges are buried in dirt and those boards behind will keep the water from pushing the tarp down flat. I did this twice.

The idea is to set the tarp so that the edges are buried in dirt and those boards behind will keep the water from pushing the tarp down flat. I did this twice.  The first time the dirt that holds the tarp down on the bottom was too high. That means when I released the tarp at the end of irrigating there would still be a dam. I have a hard enough time getting the ditch to empty that I don’t need to impede it more.

The first time the dirt that holds the tarp down on the bottom was too high. That means when I released the tarp at the end of irrigating there would still be a dam. I have a hard enough time getting the ditch to empty that I don’t need to impede it more. This is a second tarp that I set just around the corner in the ditch that goes south. I shouldn’t have to do this, but due to gopher holes, tree roots, and maybe my lack of irrigator skills it seems that one is never enough. Two tarps hold the water back better. Or at least one is a back-up for the other.

This is a second tarp that I set just around the corner in the ditch that goes south. I shouldn’t have to do this, but due to gopher holes, tree roots, and maybe my lack of irrigator skills it seems that one is never enough. Two tarps hold the water back better. Or at least one is a back-up for the other. While I was working in the pasture I saw that a couple of lambs had their heads through the electric net fence and didn’t seem to care. That prompted a search for the problem with the electric fence. I found a broken wire at the south end. I got new wire and fixed it but then found several more places where I had joined new wire to old. The more times you do that the less conductivity there is. So I took out a long stretch of the old pieced-together wire and replaced it. Low and behold, my tester showed higher strength than it has in years!

While I was working in the pasture I saw that a couple of lambs had their heads through the electric net fence and didn’t seem to care. That prompted a search for the problem with the electric fence. I found a broken wire at the south end. I got new wire and fixed it but then found several more places where I had joined new wire to old. The more times you do that the less conductivity there is. So I took out a long stretch of the old pieced-together wire and replaced it. Low and behold, my tester showed higher strength than it has in years! One thing leads to another. While I was at that end of the pasture I was bothered again by the old dallisgrass that effectively mulches my pasture. It’s one thing to mulch a garden to keep weeds from growing, but mulching a pasture is counter-productive. If you search dallisgrass in this blog you’ll find many attempts to deal with this. This time I was simply knocking it off the electric wire that is about a foot and a half up on inside this fenceline. It broke and pulled away so easily at this time (this is last year’s dry grass) that I started pulling it away by the armfuls. I didn’t have any tools or even gloves, but threw mounds of it over the fence–hey, I’ll mulch the outside of the fence and maybe keep the growth down there. That felt somewhat productive although it may not be useful at all. But at least I could see a difference in the before and after.

One thing leads to another. While I was at that end of the pasture I was bothered again by the old dallisgrass that effectively mulches my pasture. It’s one thing to mulch a garden to keep weeds from growing, but mulching a pasture is counter-productive. If you search dallisgrass in this blog you’ll find many attempts to deal with this. This time I was simply knocking it off the electric wire that is about a foot and a half up on inside this fenceline. It broke and pulled away so easily at this time (this is last year’s dry grass) that I started pulling it away by the armfuls. I didn’t have any tools or even gloves, but threw mounds of it over the fence–hey, I’ll mulch the outside of the fence and maybe keep the growth down there. That felt somewhat productive although it may not be useful at all. But at least I could see a difference in the before and after.